Our Presence is a Statistical Anomaly

A student comes in for their last Ph.D. interview. As they sit down with the professor, they are told to be proud of being the only Latina interviewee, especially since they are completing their bachelor’s degree at a lesser-known school. Not only are they the only Latina being interviewed, but they are also the only interviewee from a southern institution, not a Top 20 or private university. Unfortunately, the student recalls that this occurred at almost every interview. This story is all too common for underrepresented minority (URM) doctoral students.

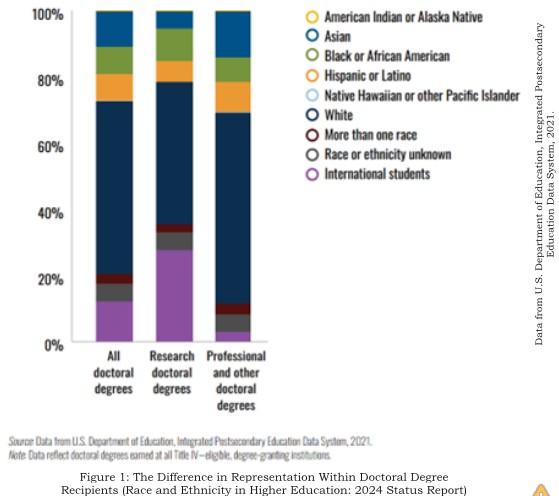

One difference between URM applicants and other candidates is that some apply to graduate school from an institution with the lowest tuition package and one that is closest to home. Despite progress made at the undergraduate level, there is still a lack of ethnic and educational representation at the graduate level . While some undergraduate programs now focus on retention and inclusion, graduate programs remain primarily concerned with achieving equity in representation.

However, this is not surprising. Testimonies from URM doctoral students across institutions reveal that their needs and challenges are often misunderstood by non-URM faculty and peers. This creates an environment where URM doctoral students are vulnerable to hostility and microaggressions. First-generation URM students also face the challenge of explaining their doctoral journey to family members who may not understand academia, which limits their support network. Additionally, due to low representation, URM doctoral students are more likely to become “champions,” taking on outreach and organizational work that creates extra responsibilities and expectations (Council of Graduate Schools, 2015).

Prior undergraduate institutions can influence the graduate programs students attend as they differ in mentorship, research access, and professional development opportunities. This affects not only a student’s decision to attend graduate school but also their likelihood of being admitted to competitive programs. In my experience, most admitted Ph.D. students at research-intensive universities—such as Ivy League or Top 20 institutions—either came from those institutions or conducted research there through internships or post-baccalaureate programs. More than 40% of Latinas and Latinos who earned social science doctorates did so at R2 universities. Latinx students from minority-serving institutions are also more likely to earn doctoral degrees from universities with lower research profiles (Fernandez, Education Policy Analysis Archives, 2020).

With low representation, a lack of belonging, and external factors such as financial hardship, familial expectations, and language barriers, academia does not make a strong case for attracting strong and diverse prospective candidates.

A Needed Shift in Academia

Academic institutions have made significant progress in representation, particularly in the last hundred years. Equality in representation across ethnicities and educational backgrounds at the graduate level is the next step toward continued progress. Numerous studies have outlined the necessary steps: creating a culture of inclusion at all levels, reducing tuition costs, centralizing professional development resources, and establishing early access pipelines for underrepresented students. Yet, a persistent gap remains between what research recommends and what institutions actually do. Here are some actions higher education scholars can take now:

o Start having difficult conversations: University leaders—such as the Provost, Vice President of Academic Affairs, or Dean of Graduate Studies—must understand the impact of inequities on student success. Even if immediate change does not occur, continued dialogue matters. Small steps, such as improved recruitment practices or targeted mentorship programs, are victories. Scholars and students must maintain a presence in institutional decisions to ensure that policies serve all students.

o Create grassroots initiatives: These could include community organizing across several departments and/or student organizations, creating a petition, launching a social media campaign for a specific initiative, hosting town halls, and establishing a podcast. This will not be easy at first, as there may not be institutional support; however, it will help provide pilot data on how initiatives can contribute to achieving equitable graduate student representation. These initiativescan enable prospective students to learn about graduate school and research opportunities early in their careers, giving them a competitive advantage. These efforts require collaboration and commitment from all, not just a select few.

o Use the alum network to your advantage: With more people, there is more influence. Reach out toalumni, collect feedback, and encourage them to speak with administrators. Generate polls to gather their thoughts and create specific initiatives. Alumni can help secure funding for scholarships and initiatives to sustain operations for years to come. This resource is often overlooked but can significantly strengthen institutional action.

Changing the Narrative

While the initiative may not be the “cure-all,” it is a strong start and can positively impact the academic trajectory of hundreds of Latinx students. These initiatives lead to institutional change and encourage current members of academia, regardless of their Latinx background, to prioritize student success for all students.

For those who think institutions will not respond to these proposed initiatives, some scholars believe they eventually will. After meeting with dozens of Latinx prospective applicants, it is clear that institutional support systems, such as recruitment programs, student groups, and professional development resources, play a significant role in where students choose to apply. Institutions that lack these resources often lack representation, which deters URM applicants from applying. Sooner or later, universities will recognize that supporting inclusion offers a competitive advantage in attracting top talent.

These institutions that make the change to serve emerging Latinx scholars will be stronger for it. By continuing to implement research findings at higher education institutions, Latinx graduate student representation will no longer be considered an anomaly, and the research field can focus on retention and future career success.

About the author

Angelina Baltazar is a Ph.D. student in Neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania, studying how tomodel Alzheimer's disease pathology using electron microscopy methods. She recently graduated from Texas A&M University with a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering.