When surveyed as a whole, this plethora of articles provides us with a broader view of the current landscape of higher education, the situation of Hispanic/Latino students within it, and how higher education institutions are planning systemic changes to rebuild, implementing concrete measures to forge successful educational and career pathways for students.

By Adriana Alcántara and Alejandra Suárez

Over the course of this year, Hispanic Outlook has presented readers with a rich tapestry of articles that include 42 profiles of higher education institutions, districts or programs – six of them contributed by their own chancellors or presidents – which range from small private colleges to large state university systems, from community colleges to graduate schools, and from well-established Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) to emerging ones. These profiles include 18 interviews with higher education leaders, who provide invaluable insights into the current trajectories and future plans of their institutions, and the personal factors that motivate them - and inspire us - to keep reaching for new heights. In addition, H.O. presented its annual lists of top institutions (which include community colleges, 4-year schools and graduate schools, and cover a range of fields including a special focus on STEM professions), essential rankings of colleges and universities across the country that enroll the largest numbers of Hispanic/Latino students or confer the largest number of degrees to these students.

When surveyed as a whole, this plethora of articles provides us with a broader view of the current landscape of higher education, the situation of Hispanic/Latino students within it, and how higher education institutions are planning systemic changes to rebuild, implementing concrete measures to forge successful educational and career pathways for students.

In addition to these profiles of higher education institutions and their leaders, throughout the year H.O. published 12 articles presenting other organizations, associations and leaders that form a part of the broader Hispanic/Latino community, in fields ranging from publishing to health and nature conservation. These articles provide a view of their valuable contributions to the community’s educational and social advancement. Finally, H.O.’s regular contributing authors and monthly features (including the new Did You Know? which shares facts about different aspects of Latin American society and culture, to deepen our understanding of our community’s shared roots) have rounded out this view by providing insights and discussions on broader political, cultural and academic issues and their relevance to the Hispanic/Latino community.

The Landscape of Higher Education for the Hispanic/latino Community: Opportunities and Challenges

According to the latest 2020 census figures, there are currently 62.1 million Hispanics/Latinos in the U.S., constituting 18.7% of the total population, or nearly one out of every five people. The Hispanic/Latino community has grown the fastest over the past decades and has now become the second largest ethnic group in the country after White non-Hispanics (57.8% of the population). Indeed, Hispanics/Latinos now constitute the largest ethnic group in California and New Mexico, and they have increased their presence substantially in areas of the country that were not traditionally Hispanic, such as the Midwest.1

Opportunities

As explored in several of this year’s articles, there are certainly reasons to be optimistic about the educational future and social mobility of the Hispanic/Latino community, which has shown dynamism and progress in many areas. The piece “A Growing Presence: Twenty Years of Hispanic/Latino Advancement in Education” explains that the number and proportion of Hispanics/Latinos in public K-12 education have grown rapidly over the past twenty years, and the percentage of Hispanic/Latino 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in 2- or 4-year colleges has also increased substantially over this period, at a faster and more constant rate than any other ethnic group. As a result, there has been a considerable leap in the overall educational levels of the community, with 89.9% of all Hispanic/Latino adults between the ages of 25 and 29 having completed high school or a higher level of studies, as compared to only 62.8% two decades ago.2

Nearly half of all Hispanic/Latino students are first-generation (the first in their families to attend college), and 65% receive federal financial aid. Although this poses a series of challenges, Hispanic/Latino students have been supported over the years by numerous institutions that have boosted educational opportunities and social mobility.

Most Hispanic/Latino students begin their higher education trajectory at community colleges, which have, in the words of former college president Gustavo Mellander, “revolutionized higher education” through their ability to serve students at different levels of proficiency, address the needs of working adults, and provide affordable career options, among many other merits.3 They are known for serving first-generation students and immigrants, channeling many thousands of students into successful employment or further studies. In the words of Dr. Reber, president of Hudson County Community College, “the community college is genuinely the gateway to the American dream.”4

Since the Higher Education Act of 1965 was passed, which included funding for “developing institutions,” Hispanic/Latino advocacy groups have worked together to include institutions that serve a certain percentage of Hispanic students as recipients of these funds. This was finally achieved in 1986, and in 1992 the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU) proposed legislation that defined an enrollment threshold of 25% and coined the term Hispanic Serving Institution.5

Currently, there are 559 HSIs across the country, which have at least 25% Hispanic/Latino students and at least 50% low-income students, and serve approximately two-thirds of all 3.8 million Hispanic/Latino college students. Excelencia in Education has defined emerging HSIs as those with 15 to 24.9% of Hispanic/Latino enrollment. These emerging HSIs have grown rapidly, with a current total of 393 spread across 41 states, compared with only 242 in 26 states a decade ago. Research has shown that achievement gaps between Hispanic/Latino and White students at HSIs and emerging HSIs are narrower than they are at other institutions. There are also higher retention and graduation rates for Hispanics/Latinos at these institutions than at non-HSIs, making them “equity powerhouses,” according to the director of higher education research at the Education Trust.6

As a result of various factors that include higher education levels and greater economic participation, Hispanics/Latinos are one of the fastest-growing groups of entrepreneurs. According to the Stanford Graduate School of Business study State of Latino Entrepreneurship, there are approximately 5 million Latino-owned businesses, which have grown by 44% over the past decade, a much higher rate than the 4% for non-Latino businesses. On average, Latino-owned businesses hire more employees than White-owned businesses and have increased their revenue more rapidly than non-Hispanic businesses. Even during the pandemic, Latino businesses increased their revenue from $2.8 billion in 2020 to $6.8 billion in 2021. Although many small Latino businesses are in food services, they have a growing presence across every industry, boding well for the economic prosperity of the community as a whole.7

Challenges

At the same time, serious gaps persist in Hispanic/Latino advancement in various areas, and much work remains to be done. Several of this year’s articles discuss the issue of Hispanic/Latino under-representation in leadership positions, beginning with the fact that, despite constituting nearly one-fifth of the population, only around 1.5 percent of elected officials are Hispanics/Latinos. Marco Davis from the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute cautions that “until we are adequately represented in leadership at all levels of government, our individual and community needs and concerns will be largely excluded from political discourse.” 8

In higher education, less than 4% of all college presidencies are occupied by Hispanics/Latinos, according to a 2017 survey by the American Council on Education, which indicates the need for better leadership pipelines.9 In addition, only 3% of university faculty are Hispanic/Latino, and only 0.7% of Hispanics/Latinos 25 and older obtain doctoral degrees, a huge gap considering that this community is the fastest growing in higher education.10

There is also a dearth of Hispanics/Latinos in key professions. In the medical field, several articles call attention to the fact that, despite notable health disparities between Hispanics/Latinos and other ethnic groups, exacerbated by the devastating effects of the pandemic, the number of Hispanic/Latino physicians has not increased. Indeed, only 7% of faculty members at U.S. academic medical centers identify as Hispanic/Latino.11 In the field of law, only 5.8% of attorneys are Hispanic/Latino, and only 12.4% of legal degrees are conferred to students from this community, according to the Law School Admissions Council.12 In STEM fields, Latino students earned only 12.2% of all bachelor’s degrees in engineering and 15.7% of these degrees in science, with Latinas even less represented, at only 8% of bachelor’s degrees in each of these fields.13

Under-representation in leadership positions and key professions results from persistent educational gaps in undergraduate and graduate education. Despite having achieved substantial progress over the past decades, as mentioned above, the Hispanic/Latino community still lags behind most other ethnic groups with regard to adult educational attainment. Among Hispanic/Latino 18- to 24-year-olds, only a little over a third (35.8%) are enrolled in undergraduate education, and this proportion is even lower at the graduate level.

This insufficient participation of Hispanics/Latinos in higher education is, in turn, the result of a series of inter-related economic, social and academic challenges that create barriers to access, retention and graduation.

In economic terms, Hispanic/Latino households have a low median wealth ($36,000), especially when compared to White households (with $188,200), according to a McKinsey study. Thus, the average Hispanic/Latino student is likely to work to contribute to the family income, depend on financial aid for college, and take on debt to pay for their education, if necessary. Indeed, 65% of Hispanic/Latino students receive federal Pell Grants, and 67% have taken out loans, incurring a debt after graduation of nearly $39,000.14

In academic terms, Mellander calls attention to the disconnect between the expectations of high school students regarding college – particularly those who are first-generation - and the actual requirements needed to access college and succeed. For example, many of these students aspire to careers that require a 4-year college degree, but enroll in general education courses rather than college-preparatory ones.15

Effects of the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had devastating effects on all communities; nonetheless, it is well-documented that the pandemic disproportionately affected minority, low-income communities, magnifying their vulnerability and exacerbating longstanding issues of under-representation.

A 2021 study cited in Martinez Ramos and Posadas’ February article found that “in California, Latinas/os/xs have higher age-specific death rates for COVID-19, compared to Whites; Latina/o/x were 8.1 times more likely to live in households at high risk of exposure (23.6 percent versus 2.9 percent).”16 A large proportion of essential workers throughout the pandemic were Hispanic/Latino. Thus, it is hardly surprising that, according to an American Psychological Association study, “Hispanic adults were more likely than others to know someone who suffered or died of COVID […] of all groups studied, Hispanic adults had the highest levels of stress.”17

In addition, the pandemic exacerbated the economic vulnerability of all low-income students, who were often forced to drop out due to the need to support the family after the death of a principal bread-earner, increased healthcare costs, child-care responsibilities as schools were closed, and other factors. An article addressing mental health cites additional studies showing that there has been a 44% increase in anxiety and depression among college students overall, and that suicide is the third leading cause of death among this group.18

As a response to pandemic conditions, higher education institutions scrambled to transfer their courses online, which allowed students to continue with their education, but also made the digital divide among different groups more evident. An ACT survey among first-year college students found that “25 percent of low-income students and 18 percent of first-generation students had limited access to both technology and the internet, whereas only 11 percent of their counterparts who didn’t identify as first generation or low income had issues with both.”19

As a result of these factors, undergraduate enrollments plummeted across all education sectors, with a particularly sharp decline at public two-year institutions, where overall enrollment fell by 9.4% in 2020, and where the enrollment of Hispanics/Latinos declined even more, by 15.7%.20

In sum, the pandemic highlighted the vulnerability of minority communities and persistent issues of under-representation. As expressed by authors Martinez-Ramos and Posadas, “the pandemic pulled back the curtain on invisible inequities that have long existed but lurked in the shadows.”21

At the same time, however, it revealed the resilience of many educational institutions and their willingness to adopt flexible measures to meet the urgent needs of their communities. As expressed by Dr. Mike Muñoz, president of Long Beach Community College, “we learned a lot during the pandemic. [It] created a proof of concept that we can adapt and make large structural changes quickly.”22 Dr. Julio Frenk, president of the University of Miami, set an example in terms of revamping the entire campus – through comprehensive infrastructural and behavioral changes -to provide safe in-person classes. In his words, public health requires weighing the risks of action and inaction, and “humans tend to underestimate the risks of not doing something”; the pandemic “accelerated change” by forcing people to make difficult decisions and spurring them into action.23

When discussing the losses and pain caused by the pandemic, Daisy Gonzales, Deputy Chancellor of the California Community College system, adds that “I’m still optimistic, and here’s why: what we have learned is, not only can we bounce back from many tragedies, but we are also incredibly resilient.”24

Broad Structural Plans and Strategies: Rebuilding and Reimagining the Future

In light of the challenges and opportunities outlined above, in the realm of higher education, 2022 could be considered a year of rebounding and rebuilding – facing issues created or exacerbated by the pandemic and trying to address these – and of reassessing and reimagining – thinking of new ways of designing and delivering educational programs that will benefit students from all backgrounds, particularly the most vulnerable, from a perspective informed by attention to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI).

Rebounding - Funding, Enrollment and Assessing Students’ Needs

One of the priorities for rebuilding at the institutional level has naturally been funding, after having been, in many cases, decimated financially during the pandemic. Institutions have made use of government grants – particularly the Federal CARES Act and related state emergency funding to mitigate the effects of the pandemic - partnered with philanthropies and businesses, and sought HSI designation to improve their standing.

The head of Loyola University New Orleans, for example, has raised over $5 million in grants from philanthropic investments to support first-generation and low-income students.25 Likewise, Tomas Morales, president of CSU San Bernardino, has focused on reaching out to funders to build the university’s endowment, which helps provide $2-3 million per year in student scholarships.26 Goshen College, a small Mennonite college in Northern Indiana, has spent many years building a relationship with Lily Endowment, Inc., to obtain grants for intercultural learning, which have placed it on the path to becoming an HSI.27

A common thread running through many of this year’s profiles is the emphasis on boosting enrollment and redressing the impact of the pandemic by gaining a deeper understanding of students’ needs. The leadership team at CSU San Bernardino, for example, where most students are immigrant or working class, conducted a student survey to identify the reasons for dropping out, and how the university could mitigate the impacts of the pandemic. As a result, six sub-committees were created to improve post-pandemic learning, which include improving individualized academic support.28 Dr. Caputo, president of DuPage, a community college in Illinois, recently assembled a task force on the Future of Learning, to assess what students need and ensure that the college is offering the appropriate modalities to students.29

Building Strong Communities – Equity and Inclusion

Given that most of the institutions profiled in H.O. serve a large number of first-generation, low-income and minority students, it is perhaps unsurprising that they have emphasized equity policies, placing inclusion, social justice and support for vulnerable students at the center of their strategic plans and structural changes.

The Tarrant County College District, which recently received its first Title V HSI grant, hopes to meet the goal of becoming a Student Ready College - one that “places the highest priority on cultivating cultures of leadership and practice that are equitable, culturally and personally relevant, and focused on the success of all students.”30 The California Community College system recently produced a ‘system impact report’ which puts social justice and equity at the center of policy reforms. For example, it proposed that the system’s CARES Act funding include veterans and undocumented students, among other vulnerable groups.31 Portland Community College has established the Yes to Equitable Student Success (YESS) framework, which creates inclusive systems and programs across the institution. President Mark Mitsui is proud of the fact that “according to (Oregon’s) Higher Education Coordinating Commission, nearly a quarter of all students who face ‘equity barriers’ to public higher education attend PCC.”32

Another example – among many - is Cerritos College in California, which aims to close achievement gaps through its recent Student Equity Plan and has received a distinction from Excelencia in Education for its institutional efforts towards achieving equity and accelerating Hispanic/Latino success.33 Long Beach Community College has also received this distinction, centering its strategies around inclusion and diversity, as has County College of Morris, New Jersey, which has increased enrollment of Hispanics/Latinos as part of a dedicated effort to increase diversity.34

All the higher education leaders and institutions profiled in H.O. hope to strengthen the connection between students and their campuses, and create a strong sense of community and inclusion. Following the central Jesuit tenet of ‘cura personalis’, care for the whole person, Marquette University in Wisconsin aims to nurture an inclusive community and “create a sense of support and belonging.”35 Dr. Reber, president of Hudson County Community College in New Jersey, is proud of the fact that a new council on diversity, equity and inclusion has created a ‘whole culture of care’, and that extensive student feedback has revealed that the college community feels like an extended family to them, to the extent that ‘Hudson is Home’ has become the HCCC’s tagline.36

Many of the leaders interviewed this year were themselves first-generation students from struggling economic backgrounds, and thus feel a deep commitment to supporting vulnerable students. Daisy Gonzales, Deputy Chancellor of the California Community College system, who grew up in foster homes, feels that serving students is her life’s purpose, and that “the function of education is to create a more just society.”37 Dr. Mike Muñoz, president of Long Beach Community College, grew up experiencing food and housing insecurity and then became a single parent, which informs every decision he makes as a leader: “The first question I ask myself […] is, ‘How will this decision impact students?’ The second question I ask is, ‘How will this impact our most vulnerable students?’”38

The president of Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Dr. Abel Chavez, with roots in a working-class immigrant family, fully identifies with the college’s first-generation students, and feels it’s his obligation to give back by supporting them and being their voice.39 Chancellor Francisco Rodriguez, who heads the Los Angeles Community College District, grew up in an immigrant working class household, and he has dedicated his life to supporting students. “I’ve never forgotten what it is like not to have professional role models or to be in an environment where opportunities are not available. I am the lived experience of the students that I’m proud to serve.”40

Strengthening Students’ Pathways to Success: Specific Measures to Support Access, Retention, Completion and Employment

Increasing Access to College

One of the first steps for increasing access to higher education is to improve outreach to high school students. Most of the colleges and universities profiled in H.O. this year have invested in programs of this sort, particularly for minority and lower-income students, as part of their broader efforts to foster equity and inclusion.

Outreach efforts include partnerships with local high school districts that offer advising for both students and their parents (which is often bilingual), to familiarize them with the academic requirements for college and the admissions process; they also often provide specific support with tests such as the SAT, and peer mentorship for first-generation students in particular. CSU Bakersfield, for example, reaches out to local children from the primary school level upwards through the Kern Pledge, a partnership with local school districts, to encourage a college-going culture for all.41 Long Beach Community College has an especially innovative approach, by reaching out to high schools with a large proportion of Hispanic/Latino students and requiring that every senior in economics and government apply to LBCC.42

Achieve Atlanta, a community organization that partners with colleges and Atlanta Public Schools, provides district-wide college advising that includes helping students with FAFSA and paying for the SAT for high school juniors.43 Several programs are aimed specifically at raising college enrollment among Latino and minority young men, such as the Texas-based Mentoring to Achieve Latino Educational Success (MALES), which provides middle and high school students with college mentors who develop close bonds, and the University of Arizona’s Project SOAR, which mentors vulnerable middle school boys to understand the obstacles they face and help create pathways to higher education.44

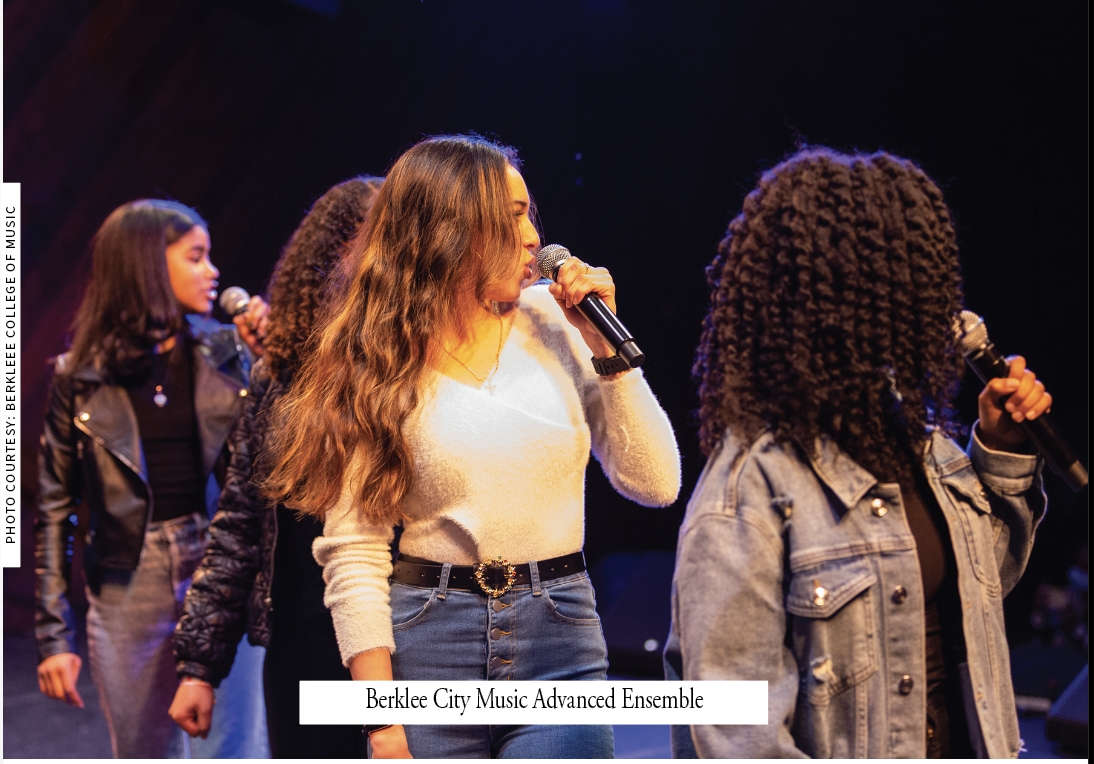

Another form of support is boosting high school students’ academic preparedness, through pre-college and dual-credit programs that fill gaps in key skills and introduce students to college-level work. Salt Lake Community College has a Summer Bridge Program that connects high school students with bilingual peer mentors, and a Pre-College Engineering Program that provides summer-intensive courses in STEM fields.45 The Berklee College of Music’s youth development program, Berklee City Music, reaches out to urban young people to empower them through a connection to their own community’s popular music, while encouraging them to develop their own creativity and introducing them to the field of music studies.46

El Paso Community College has made a large-scale effort to provide pathways between high school and college, by creating 18 Early College High School programs and 20 Pathways in Technology programs, which allow high school students to participate in dual-credit courses. The P-TECHs provide students with an early start towards earning an industry certification or degree in fields such as Automotive Technology or Cybersecurity, among many others. These programs have already shown tangible results in terms of increased EPCC enrollment and completion rates.47

Many institutions also provide targeted programs for first-generation, migrant or undocumented students – through the federally-funded TRIO-Upward Bound, CAMP (College Assistance Migratory Program), HEP (Higher Education Equivalency Program) and college-based Dreamer Centers, for example - which provide vital support for accessing college. The CAMP and HEP programs help migrant and seasonal farmworkers to earn their GED and apply to higher education or workforce training programs.

Given that financial need is a key barrier to access, higher education institutions have made concerted efforts to provide scholarships and grants to vulnerable students, either through their own resources or by drawing upon federally funded programs.

Marquette University in Wisconsin provides 40 full-tuition scholarships to Milwaukee high school seniors through its Urban Scholars Program.48 Our Lady of the Lake University in Texas has partnered with the Mexican government to provide IME-Becas, scholarships to Mexican-born students.49 County College of Morris, New Jersey, obtained $110,000 through a community-impact grant and federal funding, which it has used to support the Dover College Promise. This high-school outreach program provides scholarships and college readiness training to middle and high school students in the local majority Hispanic/Latino community.50 Achieve Atlanta provides 4,000 needs-based scholarships to Atlanta public school graduates, each worth up to $20,000.51

Other large-scale, district-wide or university-wide scholarships include the Oceola Prosper program, developed by Valencia College and local partners to increase dismally low college-going rates in the majority Hispanic/Latino county of Oceola in Florida. Through the program, 2022 county high school graduates can attend Valencia College or the county technical school tuition-free.52 Likewise, the Salt Lake Community College Promise covers any tuition costs that still remain for students receiving federal Pell grants, and uses Open Education Resources to eliminate the costs of textbooks, which has helped thousands of students.53 Finally, the Husky Promise is a full, four-year scholarship for Pell-eligible, low-income students, instituted by the University of Washington’s president in order to boost equity. About 9,000 low-income students benefit from the Husky Promise each year.54

Some states have recently enacted legislation that eliminates key financial barriers to higher education. The California College Promise Grant provides two years of tuition-free community college to all first-time and returning California community college students. This measure has had a substantial impact on increasing equitable access – in Los Angeles, for example, 5,416 students were beneficiaries of the College Promise Program in fall 2018, 79% of whom were Hispanic/Latino; this translated into a 24% increase in enrollment of LA Unified School District students in the LA Community College District.55

Perhaps the broadest scholarship program in the nation is New Mexico’s Opportunity Scholarship, which has waived tuition fees for all resident students at 29 public 2- and 4-year colleges. It is available for all state students who have maintained a 2.5 grade point average and have been accepted in any public certificate, associate or bachelor’s program, regardless of their income level or immigration status. This measure will improve access dramatically for Hispanic/Latino and Native American students, since these communities represent 60% of the state’s population.56

Improving the College Experience – Retention and Completion

The institutions profiled this year are committed to helping their students – especially the most vulnerable ones, which include first-generation, immigrant, low-income students – remain enrolled and complete their degrees, by 1) providing holistic support that includes academic and non-academic services; 2) supporting flexible credit structures and delivery systems, particularly online learning; and 3) creating an inclusive environment that builds on students’ identities and boosts their sense of cultural belonging.

Firstly, academic support is provided in a variety of ways, targeted towards specific groups. Regarding first-generation students, many institutions have created specific programs to help them navigate college. At Loyola Marymount University, for example, 800 first-generation students – the majority of whom are Hispanic/Latino – are supported by the First to Go Program, which meets academic needs through peer mentorship and help with coursework.57 Marquette University and Our Lady of the Lake University also have first-generation services or networks which connect these students to faculty and staff who understand their needs and serve as advisors.

Salt Lake Community College provides two mentoring programs specifically for Hispanic/Latino students, Somos Mas and ESL Legacy Mentors, which connects older students to incoming students who primarily speak Spanish.58 La Guardia Community College has the largest ESL program in New York City, and also offers CUNY’s CREAR (College Readiness, Achievement and Retention) Futuros Program, through which students receive peer mentorship, leadership development, internship opportunities, and connections to social services.59

In the post-pandemic environment, colleges and universities have been faced with a larger proportion of students that are dealing not only with academic or linguistic obstacles, but also with pressing social and economic ones, as basic as homelessness or hunger. Many institutions have used federal emergency funding or their own endowments to provide students with access to free food pantries, free or subsidized housing, and other forms of assistance such as childcare services, medical care and mental health counseling. In plain terms, as stated in Chaffey College’s profile, “learning cannot happen if a student is stressed out about paying rent or showing up to class with an empty stomach”: a holistic approach is necessary to support students’ ability to complete their studies.60

Indeed, Chaffey College has drawn upon millions in federal emergency funds to create the Panther Care Program, which provided more than 4,600 students with free food at special pantry events during the pandemic; it also helped with housing, and loaned Chromebooks and hotspots.61 Salt Lake Community College has hired two full-time Basic Needs Coordinators to connect students and their families to food, housing and other resources;62

Likewise, Long Beach Community College created an office of basic needs in 2018, which includes a food pantry, clothing, and even supplies for student parents, such as diapers and formula. After finding that some LBCC students slept in their cars for lack of shelter, the college provided an innovative Safe Parking program in its own parking facilities. In Dr. Muñoz’ words, “it’s not just a safe place to park, it’s also connecting them with a whole suite of services,” which include mental health counseling and internet connectivity.63 Cerritos College has also set an example by opening California’s first community college housing project exclusively for homeless students.64

Secondly, flexible hours, credit structures, and forms of course delivery – mainly, hybrid and online learning – are often adopted to boost retention and completion. Indeed, some institutions have been developing and using online courses since much before the pandemic, to provide flexible options for working students, adult learners, and student parents, among others. Coastline College has been an example of flexibility since 1976, when it devised a “distributed campus model” that offered courses at more than 100 locations throughout Orange County, rather than at a main campus, to reach non-traditional students, particularly working adults. Since then, the college has continuously adopted the newest technology available, from videotapes to online learning today.65

Likewise, Berkeley College in New Jersey started offering online courses 21 years ago and has since gained a solid reputation for its virtual programs - it has been ranked among the nation’s Best Colleges for Online Bachelor’s Programs for nine consecutive years (according to U.S. News and World Report).66 Grand Canyon University has also offered online classes for the past 17 years. Since becoming president of GCU in 2008, Brian Mueller has invested 1.6 billion in campus infrastructure and technology that has made it possible to offer online courses at a much larger scale, for a lower cost. As a result, GCU now has 90,000 online students; these include a large proportion of working adults.67

Other institutions have expanded online learning as a result of the pandemic. The transition to virtual courses on a sudden, large scale has posed many challenges, including unequal access, as discussed above. Many institutions have attempted to fill this gap by providing students with loaned computers and Wifi hotspots. Some of those profiled in H.O. also mention addressing the effectiveness of the courses by providing workshops to professors on online teaching (CSU San Bernardino) and additional academic support to help students navigate and complete online coursework (Berkeley College).

At the same time, colleges have leveraged many of the benefits that virtual learning offers, particularly for non-traditional and lower-income students. The president of Du-Page College highlights that on-line courses significantly reduced costs and time for students who no longer needed to spend gas or transport costs and long hours commuting to school.68 Chaffey College joined the California Virtual Campus – Online Education Initiative, through which students can fill out a single application for accessing online classes at community colleges across the state. This broadens the options for students who are balancing work and study, or caring for children or elders at home.69

Finally, as part of their commitment to diversity and inclusion, most institutions have encouraged the creation of clubs, services and programs that make different ethnic groups, including Hispanic/Latino students, feel culturally at home.

Some of the colleges profiled in H.O. this year have longstanding Hispanic/Latino studies programs, which provide a strong base for reaffirming students’ ethnic roots and identity. Our Lady of the Lake University, for example, is the original birthplace of the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU).70 San Jose City College was part of a movement for educational reform in the 1960s and 1970s requesting a curriculum that would reflect the multiple histories and perspectives of a diverse community. In 1974, it created an Ethnic Studies Program which included Mexican American Studies; today, the college considers this program to be “crucial to social justice.”71 Loyola Marymount University established one of the first Chicana/o Studies programs in the nation, as well as a Chicano/Latino Student Services office in 1965, sending “a message that the lives of Chicano/a people are a deeply important part of our history and have a permanent home at our institution.” This office still provides students with many avenues for exploring their culture and connecting with their identity, including a Bienvenida event to welcome students and a Dia de Reconocimiento to celebrate students’ achievements as they graduate.72

Educational activism from the 1960s is also at the root of the University of Arizona’s Spanish as a Heritage Language Program, founded in 1969, which sought to present a more linguistically diverse view than the prevailing one that ‘corrected’ students’ Spanish according to a fixed model. Around the same time, the Mexican American Studies Program was also founded, reinforcing the link between language and ethnic studies, both of which have been shown to “positively impact the academic and personal trajectories of Latina/x/o students.” Today, the SHL program still provides students with a sense of belonging and is a “model for intergenerational language recovery.”73

Other institutions have made more recent efforts to reach out to Hispanic/Latino students, as part of a general focus on diversity and/or as part of their pathways towards becoming HSIs. These efforts include creating dedicated offices and centers, organizing cultural events, and providing resources in Spanish. County College of Morris, for example, has expanded its Hispanic Heritage Month celebrations and translated major portions of its website into Spanish.74 The Los Angeles CCD has instituted a Mi Gente Graduation Celebration, which, for the first time, celebrates the achievements of Hispanic/Latino students from all nine college campuses in one gathering.75 Albertus Magnus College in Connecticut and Austin College in Texas contributed articles that highlight the personal experiences of Hispanic/Latino first-generation students who have gained a sense of community and family through various support programs.76

Finally, since “students have made it clear that representation matters to them,” in the words of the authors of Chaffey College’s profile,77 nearly all institutions have made concerted efforts to increase diversity among teaching and administrative staff, by modifying recruitment policies and making other changes; this helps provide role models and mentors for minority students.

Preparing for the Future – Work and Further Studies

Obtaining an associate or bachelor’s degree is naturally a major achievement, but it must lead to gainful employment and/or further studies for students to successfully embark on a career or otherwise fulfill their future plans. Various institutions and leaders have highlighted the ways in which they strengthen concrete connections to the job market – by providing career counseling, creating and maintaining links with employers, re-skilling adult and returning students, and launching new programs that meet the needs of the local economy.

In terms of college-based programs, Coastline College has a comprehensive approach towards career counseling, with close collaboration between its Career Center, Counseling Department and Vocational Education programs leading to a better understanding of career pathways among Hispanic/Latino students.78

Many colleges have developed effective pipelines between their graduates and local companies. The University of New Mexico's College of Engineering, for example – with a 37% enrollment of Hispanic/Latino students – has a close partnership with Sandia National Labs, one of the largest engineering labs in the nation, and with Los Alamos National Laboratory, a key part of the Department of Energy. UNM engineering graduates are also linked to large private companies such as Intel, Honeywell and Lockheed.79 Central Connecticut State University has a relationship with the aerospace manufacturer Pratt and Whitney, which provides some students with experiential learning opportunities each year, and is currently developing a collaborative agreement with well-known tool company Stanley Black and Decker.80

In the post-pandemic economy, several community colleges have seen an opportunity to reduce unemployment by re-skilling and re-directing workers towards new jobs that are in high demand. An important step in this direction is to facilitate the return of students who never completed their degrees – mainly working adults – and upgrade their skills. At La Guardia Community College, President Adams hopes to draw students from the huge pool of some 700,000 New Yorkers who started college but couldn’t complete it, through a Credits for Success Program that will provide credits for previous work so that they can re-enter the workforce with a degree. President Adams has made work-preparedness a high priority, raising 15 million to provide financial support to low-income students wishing to complete non-credit “workforce development training for key industries such as building trades, technology and healthcare.”81

Likewise, Central Connecticut State University has introduced a Bachelor of General Studies degree that will make it simpler for returning students with credits from other colleges to complete their degrees, in less time.82 Portland Community College also provides services in Spanish to students who are returning to school after ten or more years; these include evening classes, tutoring, computer training and other assistance to help reinsert them in the economy with a degree.83

Another important step taken by many institutions has been to introduce new degree programs that provide students with skills that are in high demand for the local economy. Medicine is one of these areas, and there is a dearth of Hispanic/Latino, bilingual healthcare workers, given the rising number of patients from this community. Mellander’s July article outlines eight promising healthcare occupations that are in high demand, are well-paid, and require only a certificate or associates degree.84 Many community colleges already offer these certificates; others are developing new programs in promising areas of healthcare. Central Connecticut State University, for example, has developed a new College for Health and Rehabilitation Services, and Montana State University's College of Nursing has received a $101 million donation to expand its programs and meet the growing demand for nurses in Montana.85 More than 80% of AdventHealth University graduates are naturally employed by the company AdventHealth; at the same time, however, the university operates independently and aims to meet other areas of high demand, such as nursing, through a Nursing Growth Strategy that will invest in research and development and encourage greater enrollment.86

Colleges and universities are also increasingly focusing on developing STEM professions, given the growth of these fields across the country. San Jose City College, for example, hopes to narrow the skills and wage gap between Hispanic/Latino and White workers in Silicon Valley - who earn an average of $60,000 and $146,690 per year, respectively - through the Ganas Project, which will boost career pathways in STEM.87 Through its project STEM Impacto, Moorpark College (part of the Ventura CCD) provides paid internships and financial incentives to Hispanic and low-income students in the fields of biotechnology, computer network systems engineering, and biology.88 County College of Morris has received funding from industries and the US Department of Labor to develop a popular Advanced Manufacturing Apprenticeship Program.89 Los Angeles CCD has created the first community college-based climate studies degree, and is planning to build a STEM hub for bio-manufacturing.90

An interesting example of innovative programming is Drake State Community and Technical College in Alabama, which is offering new online drone pilot training courses developed by the company Aquiline Drones. This has been created as a response to growing demand for FAA-licensed drone pilots to work in areas that include delivery and logistics, agriculture, surveying, and law enforcement, among others.91

For students who plan to continue their studies beyond the certificate or associate level, numerous programs were cited that provide pathways for lower-income or first-generation students to transfer from 2- to 4-year institutions. El Paso Community College, for example, offers an innovative online architecture program through which students can transfer seamlessly to earn a higher degree from Texas Tech.92 The nationally acclaimed Mathematics, Engineering and Science Achievement Program at Ventura College helps under-represented and low-income STEM students transfer successfully to a 4-year university. Oxnard College (part of the Ventura CCD) has created the Proyecto Exito Initiative to support the transfer of Hispanic/Latino students, through a federal Title V grant.93

There are many other examples of successful transfer programs: Portland Community College’s Future Connect Program provides participating students – 40% of whom are Hispanic/Latino - with scholarships to earn a bachelor’s degree at Linfield University.94 Since 2007, more than 40,000 Valencia College graduates - 30% of whom are Hispanic/Latino – have transferred to the University of Central Florida through the DirectConnect program, which guarantees admission to those who successfully complete Valencia’s Associate in Arts degree.95 Since 1981, more than 300,000 Hispanic/Latino students have benefitted from the California Community College District and University of California Puente Project, which aims to channel more under-represented students into 4-year degrees.96

Hispanic/Latino students have been historically under-represented in programs that enrich the higher education experience, such as study abroad, and in graduate studies. Various institutions are working to address this, as profiles of Texas A & M Education Abroad and UC Davis’ Global Learning Hub illustrate. As the top public university for study abroad, Texas A & M has also been recognized for its work to increase diversity in its programs, through dedicating about $1.5 million per year to scholarships for under-represented students. As a result, the participation of Hispanic/Latino students has increased from 15% to 23% over the past decade.97 UC Davis’ Global Learning Hub sends more than 1,300 students to locations in the US and abroad and stands out for its innovative Global Learning Seminars and Virtual Summer Internships, which facilitate broader participation. Indeed, Hispanic/Latino students are represented in a larger proportion in UC Davis’ study abroad programs than in the university overall.98

With regard to graduate studies, Mellander’s January article outlines promising fields for Hispanic/Latino students, emphasizing that higher degrees are often required in order to achieve greater social mobility in today’s economy.99 Another article profiles two key law schools – St. Mary’s Law School, where 51% of students are Hispanic/Latino, and UC Berkeley School of Law, where many Hispanic/Latino students benefit from dedicated scholarships. Both of these schools emphasize the increasing amount of resources available to Hispanic/Latino students, and the richness that these students add to their programs. According to Cathy Casiano, Assistant Dean for Admissions at St. Mary’s, there are more opportunities for Latino students now because “law schools throughout the country want to have intellectually curious students and to reach out to different populations.”100

Achieving the Goals of Higher Education – Social Mobility, Economic Prosperity and Civic Consciousness

This year’s articles provide us with an in-depth view of the complex scenario of higher education for the Hispanic/Latino community, and the measures taken to support students’ higher education pathways. There is another common thread running through these interviews and profiles – a desire to highlight the greater aims of higher education, the possibilities that it provides for individuals and their communities to improve their circumstances, foster diversity and tolerance, address important social and economic concerns, and strengthen democratic values.

Boosting social mobility and providing equitable opportunities for under-represented communities is naturally one of the main desired outcomes of higher education. The president of La Guardia Community College succinctly expresses the aims of most colleges: “Success for our students isn’t about graduating from here or from a four-year college. It is about achieving a rewarding job that sustains a family […] it’s about helping people from diverse backgrounds and needs climb the economic ladder to become the glue of prosperous communities.”101

Most of the institutions profiled this year also agree that fostering diversity is one of the main aims of higher education, since the inclusion of diverse points of view and life experiences benefits the broader society and economy. In the words of Jacki Black, director for Hispanic Initiatives at Marquette University, “diverse classrooms and problem-solving teams foster innovation, and divergent points of view can help students develop critical thinking skills.”102 From an economic perspective, Dr. Christodoulou, Dean of the UNM School of Engineering, highlights that diverse views are not only desirable but necessary for companies to engineer better products and become more competitive. He emphasizes that this is not a political opinion; rather, it is a pragmatic observation of reality: “if you get a woman and a man and an old person and a young person and you get a Hispanic and a non-Hispanic, and you get an African-American, you’re going to get different views. Most likely, you’re going to have a better design […] everybody benefits from this. That’s the future.”103

Many leaders emphasize the dual goals of providing a skilled workforce and strengthening civic consciousness. CCSU President Zulma Toro, for example, highlights that alumni are not only successful professionals, they also become “responsible citizen[s] in our country and our state, which strengthens our democracy.”104 Dr. Cauce, president of the University of Washington, echoes this sentiment: “the last few years have made it clear that we can’t take our democracy for granted. Education is important for workforce development, but it’s also important in terms of engaged citizenship and democracy.”

Dr Cauce adds that the purpose of education goes beyond individual aims for many students: “[we find] that they are going into higher education because they want to give back.”105 Indeed, a perusal of H.O.’s articles this year reveals many concrete examples of how students, institutions and leaders are helping their communities and paying forward the support they have received.

In sum, the overarching goals of higher education converge, whether they are articulated by Catholic, private schools or large public institutions. The author of Loyola Marymount University’s profile concludes with the hope that “our university always continues to seek the Jesuit Magis – the desire to do more and be better. We are grateful that our students continue to challenge us to remain true to our mission of being people for and with others, and to dedicate ourselves to the service of faith and promotion of justice. Adelante.”106 These aims are echoed by Chancellor Rodríguez, head of the Los Angeles Community College District, who emphasizes the importance of unleashing and amplifying “the greatest that is within us already, and use this tool of education to serve others and lift up our community […] Never give up. Have tenacity, resilience, and a clarity of goals and purpose. ¡Échale ganas!”107

The Hispanic/latino Community – Insights Into Broader Political, Social and Cultural Issues

Leadership

“Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute: Empowering Latino Leadership,” by Marco A. Davis, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/congressional-hispanic-caucus-institute

“AGB Institute for Leadership & Governance in Higher Education,” by Melinda Leonardo, Ph.D., August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/agb-institute

“Supporting Latinx Leaders: Campus Compact’s Newman Civic Fellowships,” by Clarissa Laguardia, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/congressional-supporting-latinx-leaders

“Why Connecting Leaders and Inspiring the Future?” by Jorge Ferraez, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/why-connecting-leaders-and-inspiring-future

Education

“Tina Fernandez, A Force at Achieve Atlanta: leveling the Educational Playing Field,” by Gary Stern, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/tina-fernandez-force-achieve-atlanta

“Latino Network: Transforming Lives through Education and Empowerment,” by Marlene López Patton and Edgar Hernández Ortiz, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latino-network

Women

“Empowering Latinas… One Woman at a time,” by Robert Bard and Lupita Colmenero, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/empowering-latinas

“Did you know: Pioneers in the Ivy League: Young Latina Leaders at Harvard,” March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/pioneers-ivy-league

“Women’s Studies/Gender Studies at Loyola University Chicago: Curious, Creative, Transformative,” by Héctor García-Chávez, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/womens-studiesgender-studies-loyola-university-chi

Medicine and Environment

“Salud América! Driving Systemic Change to Promote Latino Health Equity,” by Amelie G. Ramirez, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/salud-america

“Latino Medial Student Association: Empowering Future Latino Physicians,” by John Michel and Gualberto Muñoz, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latino-medical-student-association

“Behind a Nobel Peace Prize Nomination: Maria Elena Botazzi and the Search for an Equitable Coronavirus Vaccine,” by Sylvia Mendoza, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/behind-nobel-peace-prize-nomination

“Hispanic Access Foundation Promotes Environmental Conservation and Learning,” by Ellen Alderton, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/hispanic-access-foundation

Political and Legislative Context – News From Washington by Peggy Orchowski

Issues discussed in March - Are College Enrollment Demographics on a Cliff? Will LatinX Become Just an Academic Term? El Muro – A “Woke. Wake-up” View of Border Walls at the National Building Museum https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/6894-view-washington

Issues discussed in April - Where are the boys in College? Are College Students “Covid Sheep?” What is happening with the Hispanic Vote? https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/6910-news-washington

Issues discussed in May – Three Hispanic Cabinet members hammered by Congress and the press in April; Reading and Math Books, Student Loans Become Significant Election Issues; Two Hispanic Democrats Causing Hottest 2022 Primary News https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/6928-news-washington

Issues discussed in June - Student Debt Forgiveness, An Increasingly Debated Election Issue; Cuellar/Cisneros Race Heats Up Over Abortion; The December 1st SCOTUS Oral Argument on Abortion Explains Everything https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/6941-news-washington

Issues discussed in July - DACA at 10 years old: Why it still hasn’t (and won’t) become law in its current form; Hispanic Voters Befuddling the Pundits; Museum of the American Latino Opens as a Gallery at the Smithsonian https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/news-washington-july-2022

Issues discussed in August - Red-Flag Gun Laws Pushed by Hispanic Congressman Salud Carbajal; Congress Fails to Pass Bill to Grant Automatic Green Cards to Foreign Grad Students – Again; How SCOTUS Procedural Rulings May Affect Executive Actions https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/news-washington-august-2022

Issues discussed in September - Affirmative Action is Next SCOTUS Target; BREAKING NEWS: DACA is Now a Regulatory Law! It Changes Nothing; Chinese Foreign Student Enrollment Drops 50%, Advisors Call for More Diversity https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/news-washington-september-2022

Issues discussed in October - Student Debt Forgiveness May Be a Deciding Election Issue; Are Hispanic Voters Empowered by States Rights Issues? Surging Illegal Border Crossings Seen as a Bipartisan Opportunity https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/news-washington-october-2022

Issues discussed in November - College Enrollments Drop Overall. What about Hispanics and HSIs? Non-Citizens Voting (Including College Students) Infuriates Many Citizens; Frenzy Over Latino Vote Two Weeks Before Midterm Elections https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/news-washington-november-2022

Cultural Context - History, Arts, Music

“This Space is Yours: A Campaign for Student-initiated Programming at KJCC, New York University,” by Rebecca Portnoy, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/space-yours

“A Binational Cultural Heritage: The History of Mariachi Music Part I,” by Adriana Alcántara, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/binational-cultural-heritage

“A Binational Cultural Heritage: The History of Mariachi Music, Part II,” by Adriana Alcántara, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/6909-binational-cultural-heritage

“Lynn University – Home to One of American’s First NFT Museums,” by Frank DiMaria, June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/lynn-university-home-one-americas-first-nft-museum

“Tango Argentino: Elements and Styles,” by Alejandro Figliolo, June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/tango-argentino-elements-and-styles

“Did you know? Latin American Governments and Presidents,” January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latin-american-governments-and-presidents

“Did you know? Carnivals in Latin America,” February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/carnivals-latin-america

“Did you know? Latin American Nobel Laureates in Medicine,” May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latin-american-nobel-laureates-medicine

“Did you know? The Maya Calendar: Multiple Cycles of Time,” June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/maya-calendar

“Did you know? The Health Profession in Latin America: Top Five Regional Universities for Medical Studies,” July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/health-profession-latin-america

“Did you know? Spanish Expressions Involving Leadership,” August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/spanish-expressions-involving-leadership

“Did you Know? The First Universities in Hispanic America,” October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/first-universities-hispanic-america

“Did you know? The First Universities in Hispanic America, Part 2,” November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/first-universities-hispanic-america-p2

Broader Academic and Social Debates

“Estudios Graduados,” by Enrique Del Risco, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/estudios-graduados

“La opción de los tenaces,” by Enrique Del Risco, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/la-opcion-de-los-tenaces

“Vidas ejemplares,” by Enrique Del Risco, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/vidas-ejemplares

“Viajar,” by Enrique Del Risco, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/viajar

“Ambiente caldeado,” by Enrique Del Risco, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/ambiente-caldeado

“La libertad de la belleza,” by Enrique Del Risco, June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/6942-la-libertad-de-la-belleza

“At the Crossroads of 21st Century Education: Book Bans and Censorship,” by Frederick Luis Aldama, June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/crossroads-21st-century-education

“Nutricionistas del alma,” by Enrique Del Risco, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/nutricionistas-del-alma

“Repetimos: Estados Unidos no es el centro del universo,” by Enrique Del Risco, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/repetimos

“Otra vuelta a clases,” by Enrique Del Risco, September

“Do Students Learn Better with Digital Devices?” by Frank DiMaria, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/do-students-learn-better-digital-devices

“Cultura y apropiación,” by Enrique Del Risco, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/cultura-y-apropiacion

“Educación con asterisco,” by Enrique Del Risco, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/educacion-con-asterisco

Advice and Tips for Students

“Graduate Studies? Absolutely!” by Gustavo Mellander, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/graduate-studies-absolutely

“Did You Know? Ever Thought of Studying Abroad?”, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/ever-thought-studying-abroad

“Hispanic Males Needed in Health Professions,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/hispanic-males-needed-health-professions

“The Secrets to Finding a Part-Time College Job,” by Gary Stern, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/secrets-finding-part-time-college-job

“How Parents can Help their Child Find the Right College,” by Gary Stern, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/how-parents-can-help-their-child-find-right-colleg

References

1 U.S. Census Bureau, at https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/2020-united-states-population-more-racially-ethnically-diverse-than-2010.html

2 Did You Know? September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/growing-presence

3 “Troubled Times for Community Colleges,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/troubled-times-community-colleges

4 “Dr. Christopher Reber- Servant Leader,” by Frank DiMaria, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/dr-christopher-reber

5 “HSI Policy Formation: Advocating for Increased Latinx Presence in Education,” by Patrick L. Valdez, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/hsi-policy-formation

6 “HSIs and eHSIs 101,” by Frank DiMaria, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/hsis-and-ehsis-101

7 “Latino Entrepreneurs,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latino-entrepreneurs

8 “Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute: Empowering Latino Leadership,” by Marco A. Davis, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/congressional-hispanic-caucus-institute

9 “Senior Latinx/a/o Leaders in Higher Education: ¿Y Ahora qué?” by Jorge Burmicky and Antonio Duran, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/senior-latinxo-leaders-higher-education

10 “Centering First-Generation Identity for Latinx Graduate Students,” by Alicia A. Moreno, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/centering-first-generation-identity-latinx-graduat

11 “Latino Medial Student Association: Empowering Future Latino Physicians,” by John Michel and Gualberto Muñoz, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latino-medical-student-association and “Increasing the number of Latinx Physicians: Beyond Traditional STEM Conversations and Effort,” by Patrick L. Valdez, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/increasing-number-latinx-physicians

12 “A Changing World of Law for Latinos,” by Michelle Adam, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/changing-world-law-latinos

13 “Unicorns No More: The Promise of Today’s Latina Students in STEM,” May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/unicorns-no-more

14 “Closing Opportunity Gaps for Students of Color and from Low-income Families,” by Wil del Pilar, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/closing-opportunity-gaps-students-color-and-low-in

15 “Vanishing Teachers and Disconnects,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/vanishing-teachers-and-disconnects

16 “The Latina/o/s Past, Present and Future: Reflections on Community College,” Gloria P. Martinez-Ramos and Monique Posadas, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latinaox-past-present-and-future

17 “Community Colleges’ Latest Challenge: Mental Health,” by Gustavo Mellander, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/community-colleges-latest-challenge-mental-health

18 Ibid.

19 “Covid Consequences,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/covid-consequences

20 “Two-Year Schools Recruit and Retain Hispanics”, by Frank DiMaria, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/two-year-schools-recruit-and-retain-hispanics

21 Martinez-Ramos and Posadas, February, op. cit.

22 “Dr. Mike Muñoz: Closing Equity Gaps at Long Beach Community College,” by Frank DiMaria, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/dr-mike-munoz

23 “Dr. Julio Frenk: A University President Guided by the Ethical Mission of Public Health,” by Sylvia Mendoza, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/dr-julio-frenk

24“Deputy Chancellor Dr. Daisy Gonzales: Community College Engagement is an Act of Love,” by Sylvia Mendoza, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/deputy-chancellor-dr-daisy-gonzales

25 “Loyola University New Orleans’ Interim Leader Celebrates Inclusion,” by Michelle Adam, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/loyola-university-new-orleans-interim-leader-celeb

26 “Tomas Morales, President of CSU San Bernardino: Helping Students Rebound from the Pandemic,” by Gary Stern, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/tomas-morales-president-csu-san-bernardino.

27 “Goshen College: Values, Demographic Changes and a Transformational Grant,” by Brian Yoder Schlabach, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/goshen-college

28 Gary Stern, April, op. cit.

29 Frank DiMaria, February, op. cit.

30 “Tarrant County College District: Fostering Hispanic/Latino College, Career and Life Readiness,” by Anthony Walker, Ed.D with contributions from Demesia Razo, Ph.D., April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/tarrant-county-college-district

31 Sylvia Mendoza, March, op. cit.

32 “PCC Creates Equitable Student Success for its Hispanic Students,” by James Hill, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/pcc-creates-equitable-student-success-its-hispanic

33 “Cerritos College: Supporting Latins Student Success,” by Jose L. Fierro, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/cerritos-college

34 Frank DiMaria, April, cited above, and “Becoming a Hispanic Serving Institution – One College’s Journey,” by Kathleen Brunet, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/becoming-hispanic-serving-institution

35 “The Invaluable Contributions of Marquette University’s First-Generation Students: Unique Perspectives and Enhanced Learning Environments,” by Shelby Williamson, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/invaluable-contributions-marquette-universitys-fir

36 Frank DiMaria, July, op. cit.

37 Sylvia Mendoza, March, op. cit.

38 Frank DiMaria, April, op. cit.

39 “Del Barrio a Presidente,” by Michelle Adam, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/del-barrio-presidente

40 “A Chancellor’s Vision: Education for Equity”, by Michelle Adam, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/chancellors-vision-education-equity

41 “CSU, Bakersfield: Promoting Graduate Education in Hispanics/Latinos/xs from Kindergarten,” by Dr. Lynnette Zelezny, President of CSU Bakersfield, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/csu-bakersfield

42 Frank DiMaria, April, op. cit.

43 “Tina Fernandez, A Force at Achieve Atlanta: leveling the Educational Playing Field,” by Gary Stern, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/tina-fernandez-force-achieve-atlanta

44 “Increasing College Enrollment among Hispanic Men,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, June, at

https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/increasing-college-enrollment-among-hispanic-men

45 “Reimagining our Practices with Latinx Students at the Center,” by Richard Díaz and Alonso Reyna Rivarola, Salt Lake Community College, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/reimagining-our-practices-latinx-students-center

46 “College Pathways, Berklee City Music Creative Youth Development Program,” by Krystal Prime Banfield, June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/college-pathways

47 “Making College Possible in High School: EPCC Promotes Equity and a College-Going Culture,” by Keri Moe, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/making-college-possible-high-school

48 Shelby Williamson, September, op. cit.

49 Michelle Adam, October, op. cit.

50 “Becoming a Hispanic Serving Institution – One College’s Journey,” by Kathleen Brunet, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/becoming-hispanic-serving-institution

51 Gary Stern, March, op. cit.

52 “Striving for Impact and Prosperity at Valencia College,” by Isis Artze-Vega, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/striving-impact-and-prosperity-valencia-college

53 Diaz and Rivarola, February, op. cit.

54 “A Passion for Inclusiveness: President Ana Mari Cauce, University of Washington,” by Frank DiMaria, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/passion-inclusiveness

55 Michelle Adam, November, op. cit.

56 “Tuition-Free College in New Mexico: An Interview with Stephanie Rodriguez, State Secretary of Higher Education,” by Gary Stern, June, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/tuition-free-college-new-mexico

57 “Driving Access and Opportunity at Loyola Marymount University,” by José I. Badenes, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/driving-access-and-opportunity-loyola-marymount-un

58 Diaz and Rivarola, February, op. cit.

59 “President Kenneth Adams Seizes the Moment at LaGuardia Community College,” by Michelle Adam, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/president-kenneth-adams

60 “Chaffey College Champions Equity Initiatives for Diverse Students,” by Henry D. Shannon, Ph.D., President of Chaffey College, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/chaffey-college-champions

61 Ibid.

62 Diaz and Rivarola, February, op. cit.

63 Frank DiMaria, April, op. cit.

64Jose L. Fierro, August, op. cit.

65 “Coastline College, Helping Hispanic Student Select and Prepare for Fulfilling Careers,” by Vince Rodriguez, president of Coastline College, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/coastline-college-helping-hispanic-students-select

66 “Diane Recinos: A Post-Pandemic Leader,” by Michelle Adam, August, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/diane-recinos-post-pandemic-leader

67 “Brian Mueller and Grand Canyon University: 90,000 Online Students and Counting,” by Frank DiMaria, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/brian-mueller-and-grand-canyon-university

68 Frank DiMaria, February, op. cit.

69 Henry D. Shannon, March, op. cit.

70 Michelle Adam, October, op. cit.

71 “San José City College: Developing a Culture of Care and Connection for Latinx Students,” by Dr. Rowena M. Tomaneng and William L. García, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/san-jose-city-college

72 José I. Badenes, September, op. cit.

73 “En Comunidad: Language and Belonging in the Spanish as a Heritage Language Program at the University of Arizona,” by Lillian Gorman, September, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/en-comunidad

74 Kathleen Brunet, October, op. cit.

75 Michelle Adam, November, op. cit.

76 “Finding Family, Success, and Home Away from Home,” by Leigh-Ellen Room, October, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/finding-family-success-and-home-away-home and “Latinx is a Superpower: Life on Campus at Albertus Magnus College,” by Sarah Barr, November, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/latinx-superpower

77 Henry D. Shannon, March, op. cit.

78 Vince Rodriguez, February, op. cit.

79 “Dr. Christos Christodoulou – Creating the Next Generation of Hispanic Engineers,” by Frank DiMaria, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/top-schools-hispanics-graduate-level-stem-programs

80 “The Transformational Leadership of Zulma Toro, President of Central Connecticut State University,” by Gary Stern, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/transformational-leadership-zulma-toro

81 Michelle Adam, September, op. cit.

82 Gary Stern, May, op. cit.

83 “PCC Creates Equitable Student Success for its Hispanic Students,” by James Hill, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/pcc-creates-equitable-student-success-its-hispanic

84 “Hispanic Males Needed in Health Professions,” by Gustavo A. Mellander, July, at

https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/hispanic-males-needed-health-professions

85 “Dr. Waded Cruzado: Creating Success Together,” by Michelle Adam, March, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/dr-waded-cruzado

86 “Committed to Health Care: Edwin Hernandez Leads AdventHealth University,” by Gary Stern, July, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/committed-health-care

87 Dr. Rowena M. Tomaneng and William L. García, May, op. cit.

88 “Empowering the Latinx Community with a Commitment to DEI,” by Dr. Greg Gillespie, chancellor of VCCD, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/empowering-latinx-community-commitment-dei

89 Kathleen Brunet, October, op. cit.

90 Michelle Adam, November, op. cit.

91 “Drake State Adopts Specialized Online Drone Pilot Training Program,” by Mark B. Morre, May, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/drake-state-adopts-specialized

92 “El Paso Community College President William Serrata: Dedicated to Creating a “College-Going Culture”,“ by Gary Stern, February, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/el-paso-community-college-president-william-serrat

93 Dr. Greg Gillespie, chancellor of VCCD, February, op. cit.

94 James Hill, February, op. cit.

95 Isis Artze-Vega, July, op. cit.

96 Dr. Rowena M. Tomaneng and William L. García, May, op. cit.

97 “‘Abroad for All:’ Texas A&M Education Abroad,” by Amaris Vázquez Vargas, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/abroad-all

98 “UC Davis’ Global Learning Hub: Supporting Global Learning at an Emerging HSI,” by Nancy Erbstein, Aliki Dragona and Zack Frieders, April, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/uc-davis-global-learning-hub

99 “Graduate Studies? Absolutely!” by Gustavo Mellander, January, at https://www.hispanicoutlook.com/articles/graduate-studies-absolutely

100 Michelle Adam, January, op. cit.

101 Michelle Adam, September, op. cit.

102 Shelby Williamson, September, op. cit.

103 Frank DiMaria, May, op. cit.

104 Gary Stern, May, op. cit.

105 Frank DiMaria, March, op. cit.

106 José I. Badenes, September, op. cit.

107 Michelle Adam, November, op. cit.